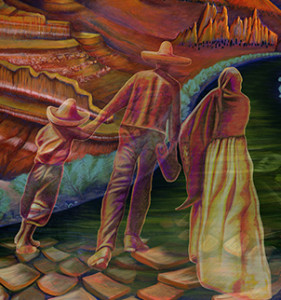

In 1998, while in residency at Harvard University, SPARC’s Artistic Director, Judith F. Baca, along with her graduate students began the production of La Memoria de Nuestra Tierra for the Denver International Airport. The 10 foot by 50 foot mural tells the Hispano-Mexicano history of the Southwest with specific emphasis on the Colorado four-corners area of the United States and Northern Mexico. In particular the mural shows the migration of Mexicans through the Juarez-El Paso border region towards the north, a migration taken by Baca’s grandparents who settled in La Junta, Colorado. A landmark work in the history of Digital Murals, La Memoria de Nuestra Tierra combines a beautifully hand painted landscape with historic photographs in a seamless blend imprinted upon the holographic-like surface of a metallic coated substrate. The mural was completed in the UCLA-SPARC Digital/Mural Lab in 2000 and is currently on permanent display at the Denver International Airport.

“My mural for the Denver International Airport, entitled La Memoria de Nuestra Tierra, is of a personal nature. My grandparents came from Mexico to La Junta, Colorado during the Mexican Revolution. They followed the course traveled by thousands of other Mexican families, from Chihuahua to the United States through the historic northern territories of Mexico (Texas, New Mexico, Colorado) via the “Ellis Island” of the southwest, El Paso. It is a story that has been little chronicled and one for which I am anxious to create a visual record.

My mother was born in La Junta, educated in Colorado’s segregated school system, and raised in its’ segregated housing in the ‘1920’s and 30’s. Recently, she was successful in petitioning the governor of Colorado to intervene in the segregated graveyard of her hometown that maintained only Anglo graves. Due to my mother’s insistence, the Governor mandated preservation and maintenance for my grandfather’s grave and those of the other Mexicans who were buried in the Mexican section of the La Junta cemetery.

The simple fact that, even in death the bodies of racially different people were required to remain separate, was what moved me to create an artwork that would give dignity to the Mestizo’s story and the stories of countless others who toiled in the mines, fields, and railroads of Colorado. Not only to tell the forgotten stories of people who, like birds or water, traveled back and forth across the land freely, before there was a line that distinguished which side you were from, but to speak to our shared human condition as temporary residents of the earth.

My great-grandfather, as family mythology recites, had water rights and with a wagon delivered water to residents of the area. His bright Spanish green eyes and red hair were his distinction as were his great large horses. He is also buried there. Perhaps it was the fact that my ancestors are planted in Colorado’s soil that caused me to wonder what was recorded there in the granules of dirt, where I believe the memory of the land might reside.

In a sense this is an excavation of the Chicano/Chicana’s complexity as indigenous people, and of their multiple identities as mixed Spaniards, Africans, and Asians, living among newly immigrated Irish, Greek and Italian people. This is an excavation and a remembering of their histories. By revealing what is hidden, through pictorial iconography in the land, this mural is a kind of Mayan map not really intended to guide your path, but instead to tell you about the road.

My research located, in the La Junta Museum, photographs of railroad workers of the region, and it is there that we found the photographs of my grandfather that will be important to the narrative aspect of the work. I conducted interviews with many people of the region and a workshop with University of Southern Colorado students on the history of the region. Students brought photos and personal narratives on their family history in Colorado to the workshop, which provided me with valuable insight for this work. I visited seven local high schools and spoke with the young people, and met with scholars and archivists.

I also learned of the Luis Maria Baca Land Grant, which of course fascinated me and has encouraged research beyond the mural to know about this particular segment of land, which is the origin of so many creeks and streams. Could this be where Seferino Baca’s water rights originated?

With the use of computer technology I have incorporated these images and documents into the mural. The landscape imagery was hand-painted at a small scale and then scanned into the computer at a very high resolution for inclusion into the mural. The final work will be a printed digital aluminum tile mural fifty feet by ten feet in length, installed in the central terminal of the Denver International Airport.

It is in the making of this artwork that my family mythology and that of so many others is finding substance in place.”

-Judy Baca

The Stories in The Mural

The Ludlow Strike

Sparked by the Colorado Coal Strike of 1913-1914, the Ludlow Massacre of April 20, 1914 left two women and eleven children burned to death by the National Guard. This final and severe effort to destroy the strike was financially supported by John D. Rockefeller. The miners of Rockefeller’s Colorado Fuel and Iron Corporation, who were mostly non-English speaking immigrants, were living a life of serfdom in the Corporation-owned mining towns. Rockefeller collected their rent, sold them their necessities, and hired officials to police potential unionization. When young, English organizer Gerry Lippiatt was murdered in Trinidad, Colorado, the miners were infuriated and voted to strike against low pay, dangerous conditions and feudal domination. In September, 1913, after the coal companies evicted eleven-thousand mine workers and their families from their huts, the strikers packed their belongings onto carts and embarked on a journey through a mountain blizzard to tent colonies set up by the United Mine Workers. For seven months they endured starvation and illness, picketed the mines to prevent the presence of strikebreakers, and defended themselves against armed assaults. Rockefeller, threatened by the persistence of the strikers, hired the Baldwin-Fets Detective Agency to break their morale. The detectives used rifles, shotguns, and machine guns to fire into the miners’ tents.

The strikers refused defeat, however, and Colorado governor collaborated with Rockefeller to send in the National Guard. The miners initially assumed that the Guard was sent to protect them, and welcomed their presence with American flags and cheers. The rude awakening hit when the men in uniform started escorting strikers to the mines through beatings and jailing. The strikers counteracted the violence by killing four mine guards, a strikebreaker and Liappiatt’s murderer, George Belcher, (a Baldwin-Felts detective) who was freed by a coroner’s jury composed of Trinidad businessmen who claimed the murder was “justifiable homicide.”

The miner’s held out through an extreme winter and feeling threatened, the mine owners called for more drastic measures. On the morning of April 20, 1914, the National Guardsmen, stationed in the hills above the largest tent colony in Ludlow (it housed a thousand men, women and children), fired machine guns into the tents. The miners crawled away and fired back while their wives and children dug into the tent floors to hide. These underground pits served as a trap however when, at dusk, the Guardsmen descended from the hill and torched the tents. The occupants fled, but a telephone linesman, going through the ruins of Ludlow the next morning, lifted the iron cot that covered a pit in one of the tents and found the mangled and charred bodies of thirteen women and children. This event became known as the Ludlow Massacre.

Why They Left

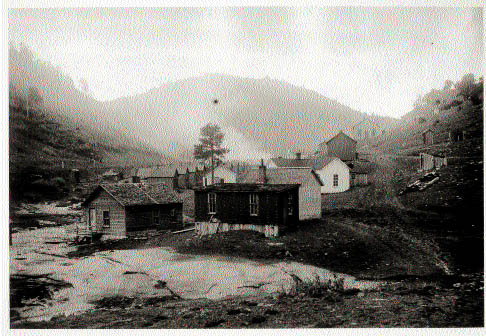

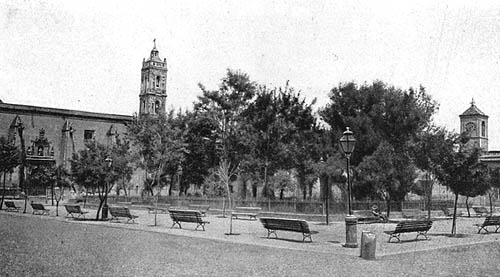

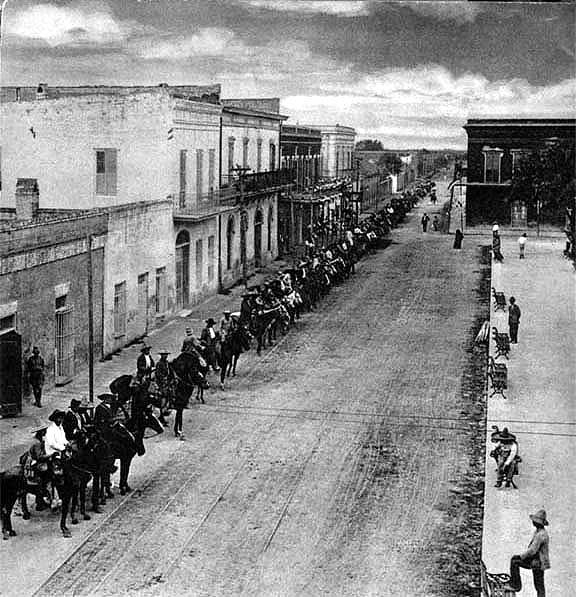

Chihuahua, Mexico-Hidalgo del Parral, La Plaza (circa 1900): Many Mexicans, including Judy’s grandparents, Teodoro and Francisca Baca, began their trip north from here.

My grandparent’s, like thousands of other Mexican citizens, sought refuge in the United States from the political and social upheaval of the Mexican Revolution of 1910. The civil war, which lasted nearly a decade, began an unprecedented increase of Mexican immigration into the United States. The Mexican Revolution marks the genesis of the story of my family in Colorado.

-Judy Baca

The Porfiriato

The period that culminated in the revolution is known as the Porfiriato. Porfirio Diaz was President of Mexico between 1876 and 1911. During that time he effectively dispossessed the Mexican population of 90% of communal land and left only 3% of the rural population with ownership of land. His policies supported foreign investment in Mexico to the extent that by 1911 the U.S. controlled 81 percent of the mining industry while Britain controlled 15 percent. Daniel Guggenheim owned the largest privately owned business in Mexico, the American Smelting and Refining Company (ASARCO). These acquisitions by foreign interest were made possible through the mining code of 1884 that enabled foreign investors to claim subsoil rights.

Foreign investment displaced thousands of indigenous people in Mexico. The Richardson Construction Company of Los Angeles purchased 993,650 acres as a result of the surveying law of 1883 in the Yaqui River Valley. The reaction of the indigenous Yaqui people to this displacement resulted in the Diaz regime violently relocating them to the Yucatan Peninsula. Workers in the urban centers also felt oppression as a result of the Diaz regimes foreign policy. In 1907 a strike at the Rio Blanco Textile factory led to mass riots, the execution of six leaders and one hundred dead strikers. The collective oppression that the Mexican masses felt from land displacement, labor exploitation, foreign control of natural resources, and political exclusion resulted in the Mexican Revolution.

Francisco Madero

was an upper class landowner and lawyer from the state of Coahuila. The Madero family owned a million and a half acres in cotton, lumber, rubber, cattle and mines. Their business in mining and smelting competed with the American Smelting and Refining Company owned by the Guggenheims. Frustrated with political exclusion from Mexico City and unprecedented foreign investment, Madero opportunistically capitalized on peasant unrest due to land dispossession and began to organize a presidential campaign around the original goals of the constitution of 1857.

Diaz, feeling threatened by Madero’s increasing popularity, put him under house arrest. Madero fled to San Antonio Texas, where he wrote the Plan de San Luis Potosi, a call to arms for all sectors of Mexican society to begin an armed Revolution against the Porfirio Diaz regime. The Plan de San Luis Potosi set November 20, 1910 as the starting point for the Mexican revolution.

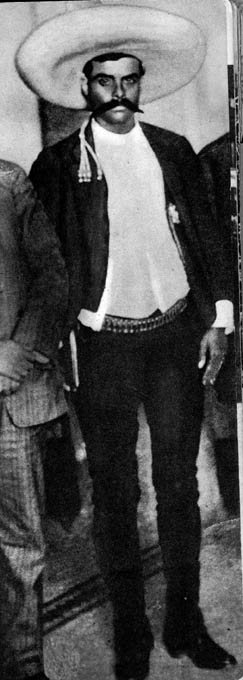

Francisco “Pancho” Villa

A revolutionary general from northern Mexico, he commanded the largest regiment of troops during the Mexican Revolution. He is most known in the Southwest for eluding a United States punitive expedition led by General John Pershing. The U.S. pursued Villa after he and his men crossed the border and raided Columbus, New Mexico in 1916 in retaliation for U.S. intervention into the war. Francisca Baca, along with many, gave him food and watered his horses when he passed through her family’s land. This is one the most highly reproduced photographs of Mexican history.

The revolutionary forces take Juarez

Americans watch the war across the border

An early and decisive battle fought during the Mexican Revolution was at the Juarez-El Paso border. On May 8, 1911 revolutionary forces led by Francisco Madero, Pasual Orozco and Francisco “Pancho” Villa confronted Federal troops in Juarez. Madero, fearful that the fighting would spill over to El Paso, called for a retreat of his troops. Villa and Orozco’s forces, already in position to attack Federal troops, disregarded the order. The battle that ensued resulted in the surrender of Colonel Juan J. Navarro and his troops.

During the battle spectators from El Paso made there way to the tops of buildings and railroad cars to witness the fighting. After the battle was over, seventeen people were either killed or wounded due to ricocheted bullets.

Emiliano Zapata

A revolutionary general from southern Mexico, he led the peasantry of Morelos in the fight for agrarian reform. Zapata is responsible for presenting the Plan de Ayala at the Convention of Aguascalientes in 1914. This plan later became the basis for agrarian reform institutionalized through the Mexican Constitution of 1917.

Led by Zapata, the peasant forces of southern Mexico, who were collectively referred to as “Zapatistas,” succeeded in occupying the Mexican capital in 1915. In Mexico City the Zapatistas were met by Francisco Villa and his forces of the north. This historic moment of the Mexican revolution marked the only meeting of Zapata and Villa, the two most famous generals of the war.

Villa and Zapata in the Presidential Palace, Mexico City

Revolutionary forces line the streets in Mexico.

The revolutionary armies were known for their ruthlessness; they were supported but feared by those they fought for.

The escalation of violence between warring revolutionary factions and federal troops presented the average Mexican citizen with few options. Either become an active participant in the fighting, an innocent victim of the war, or leave the country.

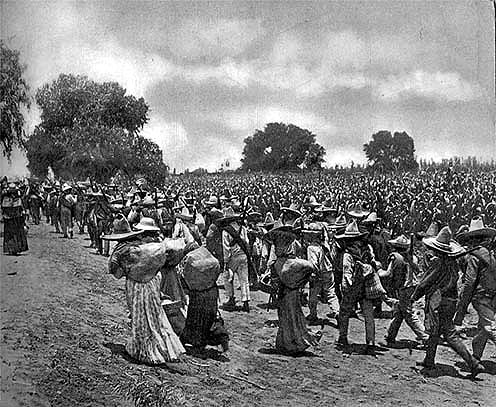

The men and women of the Zapatista forces march through the cornfields of Morelos.

The mass migrations that took place not only included families who sought to escape the violence, but also those who were participants in the fighting. Many soldiers brought their families with them into the battlefield.

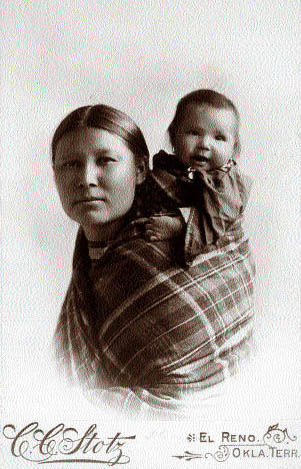

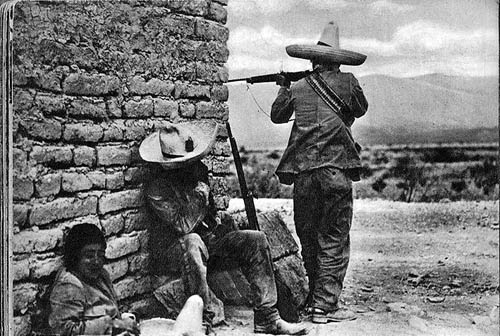

Rebel Soldiers

often burned and dynamited trains in Chihuahua and throughout the Mexican Southwest. Train riders were sent home when rebels robbed the trains. Family legend has it that Teodoro Baca walked home in his long-johns, robbed of everything except for money he had hidden in another passenger’s baby’s diaper. Teodoro had been on his way to get provisions–meanwhile, Francisca Baca, at home, was also robbed of everything except some money she hid in a water vase. It is with that money that the two went North.

Juarez-El Paso Border

Like thousands of other Mexicans, the Bacas came north believing that Juarez would provide safe haven for the duration of the war. The Juarez-El Paso region had the largest population on the U.S.-Mexico border in 1910 (114,280). The geographic and political distance from the Mexican capital enabled revolutionary leaders to lay the ideological foundations of the revolution, amass popular support, and stockpile arms without persecution from the Diaz regime.

Juarez, however, did not provide refuge from the war. When the Baca’s arrived they came face to face with the fighting at the border and were forced to cross into the United States, ultimately settling in Colorado.

A decade of civil war took it’s toll on all of Mexico, especially the children. Families were torn apart, leaving the survivors with the task of rebuilding a nation. All that was left was the promise of a better future and the hope of realizing the ideals of the Revolution.

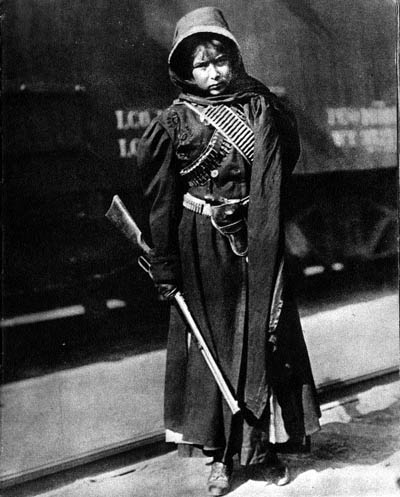

Las Adelitas: girl soldiers of the Mexican revolution; Adelita is now one of the most common girl’s name in the Southwest.

For those families that journeyed across La Frontera, their children would face new challenges. Struggling with alienation, racism, and cultural assimilation, they would join in the fight for human rights; never forgetting where they came from and why they left.

Sand Creek Massacre

On November 29, 1864 Colonel John Milton Chivington led 700 heavily armed Fort Lyon troops and volunteers into Sand Creek, located in the Southeast corner of the Luis Maria Baca land grant. Chivingtons orders were to “kill and scalp all, big and little”. The end result was the massacre of 130 Cheyenne and Arapaho people, 105 of which were women and children. The attack came unexpectedly and even shocked some military personnel. Prior to this, the people at Sand Creek were promised protection by the Governor of Colorado, John Evans, if the Cheyenne and Arapaho nations would report to Fort Lyon as friendly Indians. Two Cheyenne Chiefs, Black Kettle and White Antelope, guaranteed protection by Major Edward W. Wynkoop at Fort Lyon, led 500 people into Sand Creek, located forty miles northeast of Fort Lyon. Shortly thereafter, Major Scott J. Anthony replaced Major E. W. Wynkoop as commanding officer at Fort Lyon. The massacre that took place at dawn resulted in congressional hearings calling for an Indian Peace Commission.

During the hearings, Silas Soule, a commander of a cavalry company who refused to attack the Cheyenne at Sand Creek, testified against Colonel Chivington. His testimony was key in the committees findings that the attack on Sand Creek was “a cowardly and coldblooded slaughter, sufficient to cover its perpetrators with indelible infamy, and the face of every American with shame and indignation.” Silos Soule never had the opportunity to hear the committees findings because he was shot near his home in Denver by Charles W. Squiers of the 2nd Colorado Cavalry. Sadly, the Indian Peace Commission led to the forced relocation of native peoples to Indian reservations and did not result in the criminal prosecution of Colonel Chivington. Instead, the state of Colorado named a city after Chivington to honor his “heroic” military campaigns during the civil war.

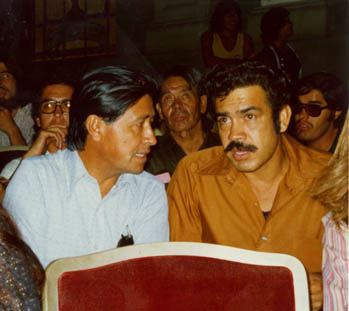

Chicano Activism in Colorado

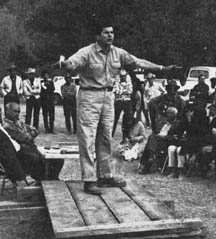

This photograph shows Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzalez at the Crusade For Justice with Cesar Chavez. The two leaders had divergent philosophies concerning the course of Chicano activism and did not collaborate in their organizing tactics. However, they were both pivotal to beginning a national dialogue about Chicano Civil Rights.

Reies López Tijerina

Reies López Tijerina founded the Alianza Federal de Pueblos Libres (Federal Alliance of Land Grants) in New Mexico to reclaim Spanish and Mexican land grants held by Mexicans and Indians before the U.S.-Mexican War. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed after the U.S. victory over Mexico, guaranteed Mexican citizens the retention of their land grants. The Alianza hoped to reclaim ownership of land through the courts of New Mexico; however, it was determined in a court ruling that the United States Congress was the arbitrator on issues of land rights based on international treaties.

Reies López Tijerina founded the Alianza Federal de Pueblos Libres (Federal Alliance of Land Grants) in New Mexico to reclaim Spanish and Mexican land grants held by Mexicans and Indians before the U.S.-Mexican War. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed after the U.S. victory over Mexico, guaranteed Mexican citizens the retention of their land grants. The Alianza hoped to reclaim ownership of land through the courts of New Mexico; however, it was determined in a court ruling that the United States Congress was the arbitrator on issues of land rights based on international treaties.

In 1967 Tijerina led a raid on the Tierra Amarilla (New Mexico) County Courthouse. This event brought the issue of land rights to national attention and became a stimulus for the Chicano movement. In 1968, Tijerina unsuccessfully ran for governor of New Mexico with The People’s Constitutional Party. Between June of 1969 and July of 1971 Tijerina was held at a Federal prison in Springfield Missouri because of his activities with the Alianza. His prison sentence led to the eventual dissolution of the Alianza. Reies López Tijerina is now retired and lives in New Mexico.