Witnesses to LA History: Estrada Courts

Witnesses to Los Angeles History: Estrada Courts came about in 1997 when the Los Angeles Public Housing Authority enlisted SPARC and Professor Baca’s UCLA class for the production of a permanent public art piece for the Estrada Public Housing Project. Estrad Courts, one East Los Angeles’ oldest housing projects, is internationally recognized and respected for its collection of Chicano murals painted in the 1970’s. Students conducted oral history interviews with 25 Estrada Courts families, researched U.S. Public Housing policy and archives, studies of sociological factors affecting the projects including economics, crime, gang warfare, urban planning, demographics and collaborated to define the issues that are represented in the imagery. Photos collected from families’ photo albums were used to depict the complex stories of immigration, teenage pregnancy, poverty, and violence that embody the neighborhood’s collective consciousness. This process resulted in the production of six 8’x 9′ digital murals that were permanently installed within the resident initiated community center by the UCLA students and their community collaborators.

Las Four

Project Description

Alma Lopéz is now a professor of Chicano Studies at UCLA

Witness to Los Angeles History: Estrada Courts also counted with the crucial participation of a young Chicana artist by the name of Alma Lo ́pez, who was initiated into digital media through her participation in SPARC. Lo ́pez then went on to become a renowned and critically acclaimed digital artist in her own right, whose work combined digital aesthetics with feminist and queer subjectivities.

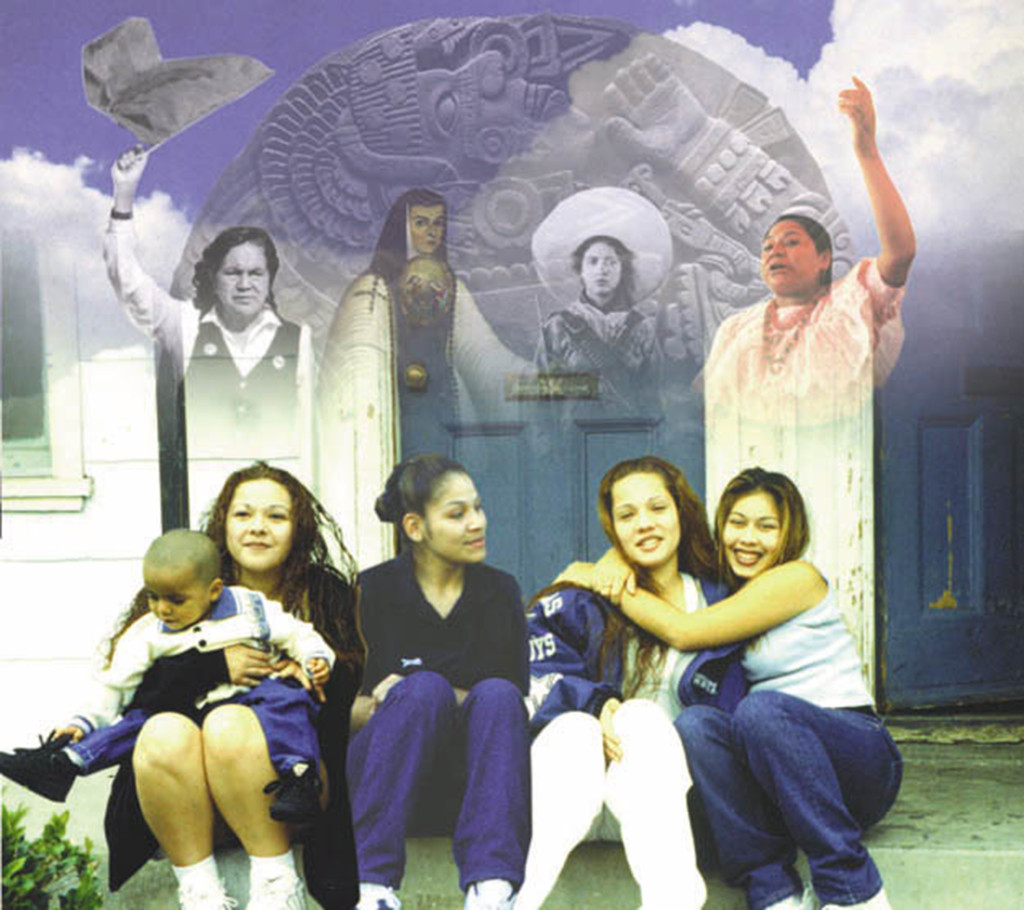

In her mural for the Estrada Courts project entitled Las Four,Lo ́pez,together with young Chicana residents of Estrada, acted as shaman-witness artivists to a radical feminist history. They also became transformative artivists whose witnessing transformed their creative and activist experiences. Lo ́pez was keenly aware of the importance of Estrada Courts as a major mural site, yet fashioned her imagery as a form 96 Learning Race and Ethnicity of feminist contestation of the predominantly masculinist aesthetics that characterized the preexisting murals there. The artist of Las Four was partly responding to another mural in Estrada, namely Ernesto de la Loza’s Los Cuatro Grandes (1993),

which celebrated the histori- cal and political contributions of four male heroes, from left to right, Ce ́sar Cha ́vez, Emiliano Zapata, Francisco Villa, and Mario Moreno Cantinflas, all of whom stood as prominent architects of Chicana/o–Mexican culture. Lo ́pez’s reaction to this type of imagery forced her to reevaluate the icons of Chicana/o identity with which she and the young women at Estrada were raised:

I grew up in northeast Los Angeles . . . during the Chicano Mural Renaissance of the 1970s and early 80s. My visual world included: wall size, meticulously spray painted black, old English, graffiti lettering; bakery and market calendars of sexy Ixta draped over the lap of strong Popo; tattoos of voluptuous bare breasted women with long feathered hair; burgundy lips and raccoon eyes painted cholas; and murals mostly depicting Emiliano Zapata, Francisco Villa, and Aztec warriors. . . . To this visual world, my contribution would go beyond the sexualized images of Ixta and the tattoo women; to create images of women parallel in presence to Zapata, Villa and the Aztec warriors.

So Alma and collaborators would replace Villa, Zapata, and the others with four eminent Chicana/Latina/indigenous activists whose historical significance has long been recognized by U.S. Third-World feminists: Dolores Huerta, cofounder of the United Farm Workers; Sor Juana Ine ́s de la Cruz, a seventeenth-century Mexican nun whose poems and plays greatly shaped baroque/colonial literature; a soldadera, female soldier of the Mexican Revolution; and Rigoberta Menchu ́, a contemporary Guatemalan/Mayan peace activist. Behind these monumental women we find Coyolxauhqui, the Aztec moon goddess, who according to Mexica scripture was murdered by her brother Huitzilopochtli, god of war, thus ushering in patriarchal rule in Aztec society. Coyolxauhqui held great metaphorical meaning for Lo ́pez and the young Chicana artists, because they interpreted the violent act directed at her by Huitzilopochtli as that “of a brother towards his sister, as the murder of male and female duality and balance, and the violent birth of a patriarchal system.” In spite of the importance that Lo ́pez and the Estrada participants gave to the figures of Huerta, Sor Juana, the soldadera, Menchu ́, and Coyolxauhqui in Las Four, their presence in the mural fades into the background in order to give way to a new generation of radical feminist practitioners, namely, the young working-class Chicana residents of Estrada. Their relationship to the figures in the background, explains Lo ́pez, is that of “spiritual leaders nourishing a future generation of young women who can claim an ancestral legacy as ancient as [that of] the pre-Columbian goddess Coyolxauhqui.” For Lo ́pez, establishing a historical and spiritual continuity between indigenous figures like Coyolxauhqui and contemporary Chicanas promotes an indigenous consciousness that is relevant to the average young Chicana living in the barrio. Learning about the story of Coyolxauhqui, in particular, helped these women understand the historical dimensions of their own gender oppression. But Lo ́pez’s use of real-life women in her work is precisely what seems to stir controversy among the communities that see her work. Shortly after its installation in Estrada Courts, Las Four was vandalized and damaged by a group of young men from Estrada who knew, and apparently disliked, some of the women in the mural, thus objecting to their representation. This episode proved that images of women’s empowerment and agency were still regarded as threatening, and even offensive, to some sectors of the Chicana/o community.